Moderation in all things

A recent radio programme was entitled “Where are the moderate Muslims?”, which began by questioning the very idea. As one young Muslim interviewed in the programme said “does being moderate mean I’m half-a-Muslim?”

The programme raised some very interesting questions about the nature of religion in a secular society such as ours – questions that are just as pertinent for Christianity as for Islam – and that are sharpened by Easter.

For a long time it was thought that religion was fading away – as economic, political and cultural stability seemed to march inexorably forward. In today’s insecure world it is no wonder that religions refuse to lie down and die; not only conservative Islam, but conservative Christianity also, and Hinduism, Buddhism and many other faiths, grow by leaps and bounds. More and more people, it seems, are seeking after the certainties traditional religion can offer.

For a long time it was thought that religion was fading away – as economic, political and cultural stability seemed to march inexorably forward. In today’s insecure world it is no wonder that religions refuse to lie down and die; not only conservative Islam, but conservative Christianity also, and Hinduism, Buddhism and many other faiths, grow by leaps and bounds. More and more people, it seems, are seeking after the certainties traditional religion can offer.

And in such a world the search for moderation in all things – especially religion – seems ever more important. If many of today’s problems stem from extremism – particularly religious extremism – then surely the way forward is moderate expressions of religion, just as moderate politics is looked to in order to win the day against, for instance, the English Defence League or Pergida in Germany.

But what is a moderate Muslim, or Christian for that matter? Someone who is only half-heartedly committed to their faith? Plenty of deeply devout Muslims lead exemplary lives. It’s difficult to imagine what a moderate Christian could even be – a Christian who only loves moderately? Who only follows Christ slightly?

Well, not one of us is good enough at following Christ, of course, but we do understand that the call to follow Christ is absolute, not moderate at all – and it’s only possible by God’s grace shown to us sinners.

But behind the language of moderation can be detected something else – what might be called privatisation. What our world really wants is religion that keeps itself to itself, that doesn’t go round seeking to impose itself on others. In the programme several young Muslims said as much – they believed in their religion with a passion, but would not dream of imposing its values on anyone outside. In such a world religious moderation equals private religion, in which every religious person gets on with their own devotion and belief without interfering with anyone else. That kind of private religion looks moderate, whatever individuals believe.

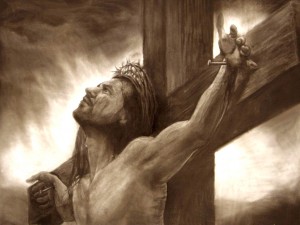

Easter blows this idea clean out of the water – rather the whole Jesus phenomenon from start to finish does. If Jesus is the eternally existing Word who came into the world; if he proclaimed a message about God’s Kingdom of love and justice; if he died to save the world and if he rose again to bring God’s new reality into being in this world, then a faith that’s rooted in him can be neither private, nor, in fact, moderate.

It is a faith that is not about practising a private religion, but about living a transformed life – and looking to see the world in every part – politics, culture, relationships, law, institutions – transformed. And it is not moderate, since it dares to believe that everything and everyone can be transformed by a love that comes from beyond and reaches to beyond any earth-bound, universe-limited love that can ever be known.

Moderation in all things? Mmmm, sounds good, and maybe a “normal”, “safe” world will always look for such moderation, but a world that has been, is being, and will be transformed by a love that was extreme enough to go through death and powerful enough to overcome it can never be allowed to settle for moderation – it must always be called to ever more extreme acts of love and selflessness and sacrifice, so that it will become the place where God’s Kingdom can be seen.

Michael Docker